As the Easter season approached, last week we sent out a letter of encouragement in the spirit of the prophet Isaiah about how through darkness we could still find help and hope on the other side of its passing.

This week, we are now ready for our museum’s next newsletter about its new exhibits. We are working on our new display cabinet for our outdoor Red Sea Egyptian courtyard. It will illustrate a number of Egyptian animal deities. Of Egypt’s 720 gods, perhaps the Egyptian Dung Beetle is one of their strangest animal deities. Its photos are featured in this week’s newsletter. Believe it or not, may I also add this Easter season that it also represented death and resurrection for the Egyptians—with the setting of the sun in the evening and the new life of sunrise after the darkness of night! Let’s explain…

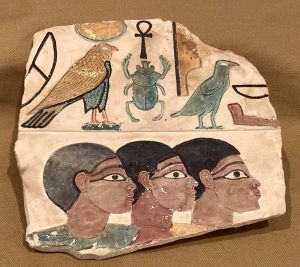

This cast of an Egyptian wall tomb painting shows a scarab beetle hieroglyph

Because the Egyptian scarab (scarabacus sacer) was often seen pushing its ball of dung containing its eggs and larvae, it was believed to be a miraculous copy the of the sun moving (being pushed) across the sky and then being buried for the night.

Because the Egyptian scarab (scarabacus sacer) was often seen pushing its ball of dung containing its eggs and larvae, it was believed to be a miraculous copy the of the sun moving (being pushed) across the sky and then being buried for the night.

The Scarab (kheperer in Egyptian) was identified with the god Khepri

This god represented the rising sun, and therefore was a symbol of eternal rebirth and resurrection. New scarab coffins were recently discovered in 2018. The two small stone coffins were really old (from 2,500 BCE) at Saqqara, the necropolis for Memphis in Egypt. One of them contained 200 dried dung beetles and the other, smaller coffin, held two mummified dung beetles, strangely wrapped in linen (in the foreground of the photo).

This god represented the rising sun, and therefore was a symbol of eternal rebirth and resurrection. New scarab coffins were recently discovered in 2018. The two small stone coffins were really old (from 2,500 BCE) at Saqqara, the necropolis for Memphis in Egypt. One of them contained 200 dried dung beetles and the other, smaller coffin, held two mummified dung beetles, strangely wrapped in linen (in the foreground of the photo).

A scarab beetle rolling its dung ball

Note how large the collection of dung and organic materials could grow in size due to the relentless rolling by its beetle, expanding like a rolling snowball. Seeing this unusual behavior seems to have helped fuel the religious imagination of a priesthood desiring to come up with stories characterizing their growing list of animal deities.

Note how large the collection of dung and organic materials could grow in size due to the relentless rolling by its beetle, expanding like a rolling snowball. Seeing this unusual behavior seems to have helped fuel the religious imagination of a priesthood desiring to come up with stories characterizing their growing list of animal deities.

A Necklace with a scarab seal

These were designed to accompany their Egyptian owners with protection and were therefore often worn around the neck for constant protection. Sometimes a scarab necklace was also hung over the heart of a mummy, with an inscription requesting it not to testify against the wearer at the last judgment.

These were designed to accompany their Egyptian owners with protection and were therefore often worn around the neck for constant protection. Sometimes a scarab necklace was also hung over the heart of a mummy, with an inscription requesting it not to testify against the wearer at the last judgment.

Unclean dried animal feces for cooking

Because the Egyptian scarab beetle was often seen pushing its ball of dung containing its eggs and larvae, it was believed to be a miraculous copy the of the sun moving across the sky. Eventually, the beetle would bury the ball in the ground until the larvae came out. Egyptians therefore believed the beetle mimicked the rising sun, pushed it across the sky every day, and through the other side of the world every night (burring it in the sands and symbolizing eternal regeneration). Scarabs were believed to ward off evil. The female beetle used her strong legs to roll the ball containing her deposited eggs. Not only was the beetle an unclean animal species, but by raising its young in feces seems it made it doubly unclean in the minds of some people!

In the Hebrew Bible there are references to drying feces from live-stock, which was then sometimes used for cooking by poor peasants. I Kings 14:10, Zephaniah 1:17, and Ezekiel 4:15 mention feces as materials for burning. The dung was collected and formed into flat “bricks” and dried.

In the Hebrew Bible there are references to drying feces from live-stock, which was then sometimes used for cooking by poor peasants. I Kings 14:10, Zephaniah 1:17, and Ezekiel 4:15 mention feces as materials for burning. The dung was collected and formed into flat “bricks” and dried.

While studying the life of shepherds in remote parts of Turkey without trees or firewood, one can still find villages storing dried sheep and goat feces for stoking cooking fires. Noting this, several years ago our Israeli tour guide, Hannaniah Pinto, with an unending sense of humor, asked for this picture to be taken of him seated in the middle of the stacks of dried feces, “to illustrate where I feel I am sitting at the end of some days of repetitive office work!”

Semi-precious stones were used to make scarab seals

This is a collection of common semi-precious Egyptian stones which were often used for carving scarab images and seals. Pictured here are stones of amethyst, amber, and various translucent agates used not only for scarab images, but also as jewelry inlay into wood, metal or leather.

This is a collection of common semi-precious Egyptian stones which were often used for carving scarab images and seals. Pictured here are stones of amethyst, amber, and various translucent agates used not only for scarab images, but also as jewelry inlay into wood, metal or leather.

Turquoise scarab stamp with hieroglyphs

Scarabs were generally between ½ inch to 2 inches in size. This size of scarabs normally were used as seals with hieroglyphs or personal names and titles engraved on the lower, flat side. Beginning in the Middle Kingdom (the time of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs) we find carvings of scarabs made from semi-precious stones (note our turquoise example in this photo). The inscription often had the name of the owner of the document upon which the scarab-shaped stamp was used. Scarabs appear as seals with symbols or personal names, sometimes celebrated weddings, battles, inauguration ceremonies, or ownership, etc.

Scarabs were generally between ½ inch to 2 inches in size. This size of scarabs normally were used as seals with hieroglyphs or personal names and titles engraved on the lower, flat side. Beginning in the Middle Kingdom (the time of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs) we find carvings of scarabs made from semi-precious stones (note our turquoise example in this photo). The inscription often had the name of the owner of the document upon which the scarab-shaped stamp was used. Scarabs appear as seals with symbols or personal names, sometimes celebrated weddings, battles, inauguration ceremonies, or ownership, etc.

Our negative impressed original scarab carving along-side its positive seal impression

The most common use of scarabs, as indicated from their archaeological context, was to indicate ownership of the contents of a jar with the impression (normally on its handle). Another use was to show the ownership of a document. In this case, string was tied around a rolled-up parchment or papyrus scroll. Moist clay was then applied by the scribe over the knot securing the tied scroll, and the underside of the scarab seal was pressed into it to be able to know if someone pried into its contents. Over the centuries, in most climates, the scroll document would have slowly biodegraded away, leaving only the impression of the clay seal remaining, without any hoped-for information about the scroll’s contents which might then be enjoyed by the dusty archaeologists after their long, tedious labors.

The most common use of scarabs, as indicated from their archaeological context, was to indicate ownership of the contents of a jar with the impression (normally on its handle). Another use was to show the ownership of a document. In this case, string was tied around a rolled-up parchment or papyrus scroll. Moist clay was then applied by the scribe over the knot securing the tied scroll, and the underside of the scarab seal was pressed into it to be able to know if someone pried into its contents. Over the centuries, in most climates, the scroll document would have slowly biodegraded away, leaving only the impression of the clay seal remaining, without any hoped-for information about the scroll’s contents which might then be enjoyed by the dusty archaeologists after their long, tedious labors.

In this photo, our museum’s ancient scarab stamp is on the right. Notice how carefully the hieroglyphic symbols were carved into its reverse negative surface. On the left scholars can read the hieroglyphic symbols of the positive seal raised from the cream-colored clay.

Reflection on whether the scarab was considered an idol by the ancient Israelites

How is it that we find beetle-shaped scarabs not only in Egypt, but also in archaeological digs all over Israel? In the Torah the Israelites were not to copy the ways of gentile idolatry to which they were exposed. The warning against copying symbols of polytheism is found in Deut. 29:16-17—

“…we dwelt in the land of Egypt…and you have seen detestable things and fetishes of wood and stone, silver and gold, that they keep” (see photos above).

The injunction against objects used in idol worship is mentioned 50 times in the Hebrew Bible. This injunction often relates to animals which are deemed unclean for eating purposes. Another injunction against eating unclean things is found in Is. 66:17—

“Those…eating the flesh of the swine, the reptile, and the mouse, shall one and all come to an end—declares the Lord.”

The prophet Ezekiel 8:10 also mentions images of these animals:

“…all detestable forms of creeping things (beetles?) and beasts and all the fetishes of the House of Israel.”

These verses have been listed from an article in The Biblical Archaeology Review, Summer, 2020, pp. 52-55 by Zohar Amar, which addressed issues of “detestable things” found in Jewish tradition.

A possible rationalization in the Hebrew Bible:

Because archaeologists find scarab-shaped stamps for use as seals pressed in clay at

many excavation sites around ancient Israel, there must have been a rationalization for their use in daily life by people who had religious traditions against idols.

Some scholars have suggested that perhaps they emphasized the second half of the Exodus prohibition more than the first half (Exodus 20:4 & 5)–

“You shall not make for yourself an idol… (vs. 4)

You shall not bow down to them or worship them…” (vs.5)

In this view, the forbidden act would not be possessing the image, but would be to bow down and worship it. The same logic might explain why some Hellenized Jews felt it was alright to use coins bearing human form, or having mosaic floors with human or animal forms on them. More conservative Jews would probably have entirely avoided such coinage or living in houses with such floor designs.

A possible rationalization in the New Testament:

Saint Paul discusses this same issue when speaking about eating meat from the market which had been “offered to idols” (Corinth had over a dozen temples.) (I Cor 8:4-10):

“Hence, as to the eating of food offered to idols, we know that no idol in the world really exists, and there is no God but one… It is not everyone, however, who has this knowledge… But take care that this liberty of yours does not somehow become a stumbling block to the weak. For if others see you, who possess knowledge, eating in the temple of an idol, might they not, since their conscience is weak, be encouraged to the point of eating food sacrificed to idols?”

It seems that in both Old and New Testament times there were some faithful adherents

who took their traditions literally and would not attempt to appreciate or even touch something that might be considered an idol. On the other hand, there might be another faithful adherent whose appreciation was “as art,” and did not, shall we say, believe in the metaphysics of the image. For them, “Look at that beautiful scarab!,” or, “That looks like a great steak on sale in the market!” For Paul, the important thing was to try to show sensitivity to where “the weaker brothers” are coming from, possibly helping them find new joy in expanding their horizons.

Inevitably, we may have some visitors to our museum who object to us having displays which attempt to illustrate what people surrounding the Israelites believed about their world. We would hope they might be able to one day rejoice in a wider belief that the God Most High is not threatened by a little beetle who has interesting ways of preserving and nourishing its young.